A New Paradigm for Internal and External Martial Arts

Internal vs. External – The Rift

I became acutely aware of the rift between the internal and external martial arts about four years ago (2004) – I am certain it has existed long before my meager powers of observation detected it. It appears to still be in full effect today.

Over the last 22 years, I have studied both so-called “internal” and “external” systems of many flavors. I have long subscribed to the philosophy that Bruce Lee made famous – i.e. the “Absorb what is useful…” philosophy. But one day it just hit me: no one – at least in my searching – had used this philosophy to overtly embrace both the internal and external martial arts. It seems that internal martial artists stick to the internal systems and external martial artists do the same with external systems. (Exactly what makes a system internal or external, we will discuss shortly.) Each side of this rift wants to experience many different systems and incorporate them into their overall repertoire. An external practitioner may train in three, four, five or more systems – but they will all be clearly external. The same condition exists for internal practitioners – most begin with T’ai Chi, and if they then wish to explore the full martial path of the internal arts, they branch out to Hsing-I and perhaps Ba Gua; in rare situations, some will include Aikido. Clearly the choices on the internal side are limited. The reasons for this apparent prejudice are mostly based on perceptions, motivations, expectations, and – within the limited martial arts community – cultural bias. By cultural bias, I am not referring to any specific nationality, ethnicity, race, etc. – I am speaking about the behavior and attitudes of martial arts practitioners. In this article we will explore these topics and the background information necessary to fully understand them. This article will also propose some new and interesting ideas that will hopefully add to the creative evolution of the martial arts.

This article will discuss the following topics:

- Definition and description of internal and external

- The current landscape of martial arts training philosophies

- Some of the reasons for the rift between internal and external systems

- A more correct definition of the terms “internal” and “external”: i.e. principle-based and technique-based, respectively

- Why a martial artist should explore both principle-based and technique-based systems

Historical Significance of Internal and External

Let’s break this down into two parts: 1) the historical origins of the labels “internal” and “external” martial art – and 2) what these systems really are – regardless of the historical origins of the label – in a modern context. Here we go:

Historical context of the labels internal and external martial art: The terms “internal” and “external” as applicable to martial arts originated in China. In China’s vast panoply of martial arts systems, there are two major categories: Shaolin gong fu (and all its descendants) and Wudang martial arts. Out of all the Chinese martial arts systems, there are only three martial arts that are considered original internal arts: Taijiquan (T’ai Chi Ch’uan), Pa Kua (Ba Gua) and Xingyi (Hsing-I). [Note: The names of the martial arts systems used in this sentence that appear in parentheses use the Wade-Giles version of Romanized Chinese words. Those not in parentheses are in the Pinyin version of Romanized words.] The reason they are considered internal is because these arts originated from within native Chinese Taoist temples in Wudang. I.e. – they are internal to China. All other Chinese gong fu systems can trace their origins to the Shaolin Temple. Tracing the history of the Shaolin Temple and the martial arts that evolved from this Buddhist temple reveals the fact that an Indian monk – Bodhidharma (Da Mo in Chinese) – came to the Shaolin Temple and brought with him the exercises he learned as a member of the Indian Kshatriya warrior class, which he then taught to the Buddhist monks at Shaolin. These original exercises, I am sure, bare little resemblance to what became known as Shaolin gong fu – but this is where and how they originated. “So what?” you may ask. Here’s the point: since Bodhidharma was a non-Chinese – he was Indian – the martial arts from Shaolin, and all of its descendants, are considered to be external. So the original meanings of external and internal had nothing to do with “hard” or “soft” types of martial arts.

What internal martial arts really are: In modern context – given the misuse of the label “internal” martial arts to be associated with “soft” martial arts (how can any martial art be soft?) – a different usage of the phrase “internal martial arts” is necessary vs. the historically accurate definition. So, today we can label internal martial arts as those systems/styles that focus on developing inner strength and power. What is inner strength? It is commonly referred to as “ch’i”, “ki”, “qi”, “prana”. But there is much more to it than this. Breathwork, sensitivity, tendon-strength vs. muscle strength, body mechanics and nerve functions. Blending and shaping with an attacker’s energy and using it against him, subtle forms of movement to produce great power, etc. From a practical applications perspective, internal martial arts are based upon universal principles. Principles are by definition absolute. Application of these principles in a combat environment is what the internal martial artist strives for. Examples of this type of martial art include: Taijiquan, Pa Kua, Xingyi, as well as Aikido/Aiki-based arts, Systema, and any martial art – even those considered external – that follows a principle-based framework. You are probably wondering what, exactly, are these “principles”; we will get there soon.

What external martial arts really are: Again – in today’s context – external martial arts are the “hard” martial arts. External martial arts are those systems that develop direct responses to specific scenarios, foster the growth of physical attributes such as strength, speed, endurance, etc. and seek to provide the practitioner with a wide array of techniques that can be applied against the opponent. External systems are typically linear in attack and defense (although not always), and often apply a “force vs. force” attitude. Raw aggression is often encouraged and/or produced from extensive training in external systems. External practitioners seek to overwhelm their opponents by sheer physical prowess. Examples of external martial arts include: Karate, Tae Kwon Do, any kung fu system, Muay Thai and Krav Maga (this is not an exhaustive list).

If someone asked me to give the briefest possible one-line statement to describe the difference between internal and external martial arts, I would probably give this: “External martial arts contest for space; Internal martial arts do not.” One can extrapolate a great deal from this one sentence if it is analyzed thoroughly – which I leave for you to contemplate on your own.

What’s more effective?

That’s the big question, isn’t it? And this is where the rift that I spoke of in the opening lines of this article becomes apparent. Although many martial arts practitioners strive to branch out and learn as much as possible, most will only explore one side of this rift. In today’s world, the large majority of practitioners follows the MMA philosophy and therefore – obviously – studies external systems exclusively. (This touches on another subject that I feel strongly about – i.e. – fighting vs. combat. I have an article published on this subject also.) And most internal practitioners have jumped on the health-and-wellness bandwagon. This creates polar opposites in philosophy and practice and further widens the existing rift between internal and external systems. Practicality must be accounted for and the external practitioners perceive no real-world value within the internal martial arts because they only have the health and wellness practitioners as examples.

Would I use T’ai Chi push-hands against a MMA opponent? Of course not. But – I would absolutely use push-hands principles against any combatant or fighter – as the situation dictated. Sensitivity, reception/blending of energy with a proper response, relaxation, moving from your center – all of these are principles that would enhance any martial artist’s performance.

In my opinion, and from my personal experiences, here are my observations on this topic:

- The MMA mindset is too focused on competition and fighting, as well as fostering an attitude of unnecessary violence and aggression. I say “too focused” because this type of training can actually work against you in combat

- The current internal mindset is too focused on health benefits alone and is ignoring the efficacy of the internal arts as martial systems. By this I am referring to the touchy-feely new age fluff that has surrounded T’ai Chi and Chi Kung in particular.

- The perception exists that internal martial arts are ineffective as actual fighting and self-defense systems

- Both internal and external systems offer huge benefits to the practitioner who is willing to explore them. The “Absorb what is useful…” philosophy should extend to all potential systems, not just the ones Bruce Lee explored himself. (It is a little known fact that the first martial art that Bruce Lee studied was Wu style T’ai Chi. This author believes it contributed in a significant manner to the foundation of Bruce’s amazing internal power – i.e. his “one-inch punch” and other feats of power he demonstrated). Examples of these benefits:

- T’ai Chi push-hands develops exceptional sensitivity and the ability to blend with an attack. I have found this to be an amazing complement to Wing Chun trapping and sticky hands, as well as Kali hubud drills

- Ch’i is real and it can be developed. Just as it takes time to develop musculature and endurance by proper training, so too can one foster ch’i and use it in actual conflict scenarios (and I don’t mean tossing someone across the room without touching them – there are very practical applications of ch’i)

- The Breathwork exercises in the internal systems are outstanding and help develop endurance, flexibility, power and the ability to maintain a calm demeanor under duress

- The footwork developed in external systems is essential to any serious martial artist. Combine this with the balance and movement principles of internal systems and you have a potent overall mobility package

- Having a core set of techniques for strikes, counters, locks, etc. at your immediate disposal is a must; external systems are known for these types of drills

- The physical conditioning of external training is invaluable and should be included in any martial artist’s regimen. I don’t buy the adage that musculature blocks the flow of ch’i – I think I am living proof that it does not. On the other side of the coin, however, we don’t want to be excessively muscled, either. Form and function are the key factors.

- I don’t want to completely disregard the health benefits of internal systems. There are amazing examples of increased and sustained health as a result of training in T’ai Chi or some other internal system. But the health benefits should not be the driving factor of training. If you practice any internal martial art faithfully and correctly, the health benefits will become manifest of their own accord. In fact, I offer the argument that one cannot obtain the fullest level of health possible from the internal systems unless one trains in the internal system as a full martial art – complete with fighting applications, sparring, weapons, etc. Plus, the physical recovery aspect provided by the internal arts – T’ai Chi in particular – are something every external practitioner should consider. I have found that I recover so much faster and more completely if I keep up with my internal practices after a hard workout; a Chi Kung session or a slow, easy Yang short form always does the trick. If I don’t do it, I am much sorer and slower the next day. Those martial artists over 30 should really think about this – although any age group will benefit from this.

Ultimately, any martial art system – internal or external – can be very effective. It often comes down to the skills and talents of the individual, his/her teacher and the methodology of training. Personally, I feel that I have expanded my horizons considerably by training in both internal and external systems and drawing on the best of each philosophy.

Although lifelong training in internal systems can cause amazing capabilities to become manifest in the practitioner, usually in the manipulation of ch’i or whatever term you want to give to intrinsic energy, this end-state should not be the focus of one’s training. These skills are real. The problem is, those who publicly profess to have them are usually bogus. I have met two masters who truly possess these internal skills – they do not boast, or overtly advertise having these capabilities. Often, once a practitioner attains this level of skill, he/she has transcended so much of the mundane they have no desire to overtly broadcast these skills. And they realize that sharing this knowledge is only meant for a select few. That said, from the very first day of training in the internal arts, there are practical applications that can be applied to any conflict scenario.

Even Pavel Tsatsouline, the Russian kettlebell and physical performance master, who is well-known for his “hard-living comrades” philosophy, pays much respect to the internal principles, so long as they are applied correctly and practically. Check out his web site (www.dragondoor.com) and especially his book The Naked Warrior.

Internal or External?

Let’s take Hsing-I as an example. If a practitioner learns all of the physical components of Hsing-I and applies them correctly in a combat scenario – is this practitioner performing internal or external martial arts? From a physical observation perspective, it is almost impossible to identify. For Hsing-I to be used as it should be (i.e. an internal combat system) it requires the practitioner to directly apply the internal principles that make Hsing-I so effective. Hsing-I techniques by themselves are still very effective as far as technique is concerned, but what makes Hsing-I truly powerful is its internal features. I deliberately chose Hsing-I as an example, because to the untrained eye, Hsing-I looks very much like an external system – and again, it is essentially just an external system if one applies only the physical techniques of this art. For Hsing-I to be truly internal requires the application of internal principles. Modern Aikido suffers from a similar situation; it attempts to communicate the strong internal principles upon which Aikido is dependent, yet it mostly teaches Aikidoka a limited set of joint-locks, throws and pins. These techniques are very effective, to be sure, but in my experience, very few Aikido practitioners have come close to the real internal principles that are necessary for Aikido – even at the advanced Dan ranks. This is why I like to say there are no internal martial arts, only internal martial artists. I would like to extend this conversation to include some personal experiences regarding internal arts:

- I had trained in Aikido for some time at a few different dojo and had attained brown belt rank at one of them. I considered myself an above average aikido student and felt I understood the true principles of Aikido. Eventually I decided to branch out and examine other Aiki-based arts, especially aiki-jujutsu and kenjutsu. During my first night in class at the aikijujutsu dojo I realized how little I grasped these principles. The class was doing an ikkyo/nikkyo-like movement (to give it an Aikido label). I thought “I know how to do this”. But when I tried to apply the technique as I understood it, my partner barely budged. My move was mechanically correct, but it was flawed in principle (this could also be a commentary on some of the training practices at many Aikido schools – i.e. your partner not keeping you honest). Once it was explained to me how to apply the principle to the technique I was astounded at the difference. I know there will be some Aikidoka that will say I was never taught the correct movements originally, but I will disagree. I studied Aikido at some very respectable and very traditional schools and what was taught at the aikijujutsu dojo was very different (with the exception of my very first Aikido dojo). The movements look the same, but are fundamentally different. Eventually – after practicing at this dojo for a while – I came to understand the absolute correlation between the sword and the empty hands techniques in Aiki-based arts. Real aiki-jujutsu is a direct off-shoot of real kenjutsu. The word “real” in the previous sentence cannot be overemphasized and has multiple facets, which we cannot get into here. Once a practitioner absorbs the fundamental and harmonious aspects of training with the sword (not bokken, but the sword), the aiki jujutsu principles become self-evident. In our kenjutsu dojo it is said “The mind makes the cut” – a truer statement cannot be given in the world of internal martial arts.

- At the core of most internal systems is the concept of relaxation. This almost seems like a contradiction to fighting and combat. But I have come to believe this is what makes the real difference in combat: the ability to be relaxed (i.e. as relaxed as is possible) under stress. Internal arts often talk about being and staying relaxed, but few of them build drills and exercises where it can be learned and applied. Breathwork is the cornerstone of this concept and must be trained correctly to realize results. Also – for one who has trained for a long time in, or exclusively in, external systems – learning how to relax during combat drills is very difficult. But the rewards of this type of training are tremendous. I had a lot of “un-learning” to do in this area when I started doing internal arts seriously. But once the breathwork becomes automatic and the principles of energy movement are enforced, the results speak for themselves. It is often an epiphany moment for practitioners when they fully grasp the power of this type of training. Just a simple thing like delivering a strike becomes completely different and much more powerful; it really must be experienced to comprehend.

On the converse side of this discussion is the external martial artist who cultivates internal principles without directly attempting to. Here are two examples:

- To my knowledge, Guro Dan Inosanto has not studied any of the classical internal arts (T’ai Chi, Bagua, Hsing-I, Aiki-based arts) yet he has clearly developed amazing internal power. He once demonstrated a Silat move on me (he was 71 at the time, btw) and he moved me with such ease and lack of physical effort – I was quite surprised (for the record, I weigh about 215, and Guro Dan weighs about 160). It felt exactly like movements I had received from my T’ai Chi teacher or my Aiki jujutsu sensei on countless occasions. The move that Guro Dan executed would clearly be categorized as external; but he executed it with an internal power that made the external technique flow so much more effectively. I believe this is why so much of what Guro Dan does looks to be so fluid and effortless. Yes, he has studied and mastered several external systems over several decades so the physical execution of the techniques is completely burned into his neural pathways – but in my opinion, he has also acquired a high degree of internal power resultant from those decades of training. The conclusion is this – principles will always become apparent and incorporated into the practitioner’s skill set if they earnestly train in martial arts – internal or external – for a considerable length of time. From the external practitioner’s viewpoint, the countless repetitions of techniques over time eventually opens doorways of awareness into what makes the techniques work so effectively. These doorways put the student on the path of understanding the underlying principles of Universal Law and the Harmony of Nature. Internal martial artists begin the study of these principles from the beginning and over time they apply these principles to many different techniques. Eventually they come to understand that the principles themselves are useless unless they can be applied to techniques and movement without thought or focused mental effort.

- Sifu Francis Fong. Sifu Fong is a renowned Wing Chun master. I think everyone will agree with me that Wing Chun is an external martial art. But Sifu Fong has developed an astounding level of internal power. I would list in this article some of the things I have seen Sifu Fong perform with my own two eyes, but it would sound ludicrous when you read it. Suffice it to say that Sifu Fong’s internal energy is legendary. Go to one of his seminars and perhaps you will be fortunate enough to experience it. This is another example of an external practitioner developing outstanding internal power.

I hope the point is made clear: it really doesn’t matter if you train in internal or external systems – or, in my vocabulary – principle-based or technique-based systems – so long as you practice diligently and honestly, from a desire to become the best martial artist and best human being you can become. Then the deep, underlying principles of Universal Law will become apparent to you and you can taste those moments when you are in complete harmony with this Universal Law and understand why you walk the Warrior Path.

A Proposed Paradigm

I know the terms “internal” and “external” martial arts will probably never go away. But I am proposing a new paradigm, a new nomenclature for describing them in a more accurate manner. Let’s lay a foundation first:

Definition of Terms

Principle

(Merriam Webster’s definition): 1. a comprehensive and fundamental law, doctrine, or assumption 2. a primary source

(Dictionary.com definition): 1. an accepted or professed rule of action or conduct 2. a fundamental, primary, or general law or truth from which others are derived 3. a fundamental doctrine or tenet; a distinctive ruling opinion

Technique

(Merriam Webster’s definition): the manner in which technical details are treated (as by a writer) or basic physical movements are used (as by a dancer); also : ability to treat such details or use such movements <good piano technique>

(Dictionary.com definition): 1. the manner and ability with which an artist, writer, dancer, athlete, or the like employs the technical skills of a particular art or field of endeavor. 2. the body of specialized procedures and methods used in any specific field, esp. in an area of applied science. 3. method of performance; way of accomplishing. 4. technical skill; ability to apply procedures or methods so as to effect a desired result.

I give definitions not to insult anyone’s intelligence, but, firstly, to ground myself in exactly what I am attempting to communicate, and secondly, to ensure we all have the same understanding of the material being discussed.

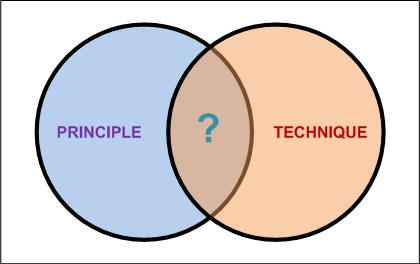

So, with these definitions in mind, let us continue. One topic that I wrestle with is the philosophical approach to blending principle and technique. Are they two separate entities that must be independently utilized in training, or is there an intersection of these entities that must be accounted for? I suspect it is both and neither.

What do we call the intersection point of Principle and Technique? Does it even exist? Or does each reside in its own sphere unaffected by and not influencing the other?

Let’s continue to elaborate on what principles and techniques are:

- Techniques must adhere to principles – if we accept that principles represent universal laws

- If techniques are performed with full knowledge of the underlying principles, they should be more powerful. Techniques performed as conditioned responses (although still adhering to nature’s laws) will never be as potentially powerful as those done by an adept who fully understands the underlying principles

- Techniques are specific in application

- Principles alone accomplish little – application and enforcement of principles is the key; this is where techniques are essential

In a nutshell, principles are abstract concepts that must be applied physically to observe empirically. This physical application of principles is the techniques themselves. The most effective techniques are the ones that most closely adhere to the universal principles.

Principles

We have spoken much about principles, but what principles are we actually talking about? Here we will discuss the most important principles (in this author’s opinion) in the martial arts:

- Internal Energy cultivation – what is known as ch’i, qi, ki or prana. Developing your internal energy stores is a must.

- Movement of energy – understanding how energy itself moves, and then how to move it directly, and how to move with it.

- Acceptance – at a spiritual, mental and physical level. Acceptance is the first step towards relaxation and not contesting for space.

- Yield, Blend and Flow – very much related to – but still separate from – movement of energy. These principles are most closely related to techniques and are the driving force behind performing techniques in a better way.

- Breath – this is probably the single biggest principle. Proper breathing and breath-related training is essential to developing a thorough understanding of principles – and techniques.

- Relaxation – all true power comes from relaxation and the balancing and relaxation and tension within the body. And to be clear – when we say “relaxed” we do not mean being limp or sleepy or docile. Relaxation brings the highest state of awareness and allows the maximum amount of power to be delivered when needed.

- Body mechanics – having a fundamental understanding of how the body operates and where critical mechanical and energetic nexus points are located.

Techniques

Now that we have listed the principles that are the foundation of the internal systems, let’s examine the techniques that are the pillars of the external systems.

- Counters and blocks – the various ways of intercepting and responding to an attack in a force vs. force paradigm.

- Strikes – any of the ballistic hits from the hands, feet, elbows, knees, etc.

- Joint-locks, pins, takedowns, throws – how to use the body’s structure against itself; and knowing the weak points of the body’s structure.

- Combinations – putting together different series of strikes –

- Footwork – perhaps the most important aspect of external training. Footwork is the key to so many areas in both external and internal training, but is mostly evident in external techniques.

- Speed, strength, endurance and flexibility – although not specific to external systems, these physical attributes are most evident in the training of external martial artists.

Blending

A comprehensive, effective training regimen must focus on the development and blending of both Principles and Techniques. Unless both of these areas are studied, understood and absorbed, the practitioner will not advance as far as possible in their martial studies. A magnificent side-effect of studying the martial arts in this unique manner is a deeper understanding of life itself, allowing the practitioner to excel as a human being as well as a martial artist. .

Summary

In this article a re-thinking of the traditionally-labeled Internal and External martial arts was proposed; that what have been called internal martial arts be labeled as principle-based martial arts, and external martial arts be labeled as technique-based martial arts. The one stipulation that comes with this proposition is the internal systems must be practiced as martial arts and not as an alternative health method. As we have already said – if the internal martial art is practiced as a combat art, the health benefits will become manifest of their own accord, and to their fullest extent.

My personal experiences in the arts have shown that my external techniques have been greatly enhanced by knowledge of internal principles. And my understanding of the underlying principles has become more deeply entrenched by studying and absorbing many different types of techniques. If it appears that I have favored the internal systems in this article, it is only because I believe there is great potential latent in the internal systems that could elevate many external practitioners’ skill sets. I also hope to keep the “martial” in the internal martial arts, because it seems to be slipping away.

A Final Comment – Is there a martial art that combines both Principle and Technique?

In my opinion – yes. That martial art is Systema – Russian martial art. I will not go into a lengthy discourse on Systema, but I can tell you it has opened new doors for me in many ways. If you want to explore some of the internal principles that we have discussed here in a directly applicable manner that is 100% geared towards combat and fighting, I recommend looking into Systema. Here is the web site for Systema: http://russianmartialart.com

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.